Stripped of their rights, the last wall of Palestinian resistance is culture, says owner of a Jerusalem bookshop.

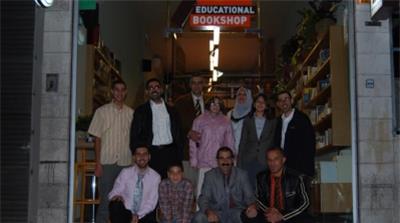

Shortly ahead, across the road, is another bookstore and cafe, also titled the Educational Bookshop. Both belong to the Jerusalem-based Muna family; the first sells Arabic books and stationery while the latter sells English books. “The bookshop started with one bookseller: my father. Now we are six brothers who read, recommend and sell books,” said Mahmoud Muna, manager of the English bookshop.

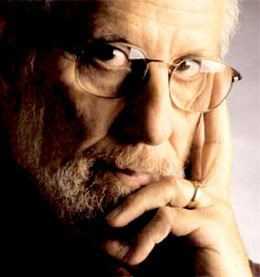

Upon entering the English bookstore, a shelf stocked with books by noted Palestinian academic Edward Said catches the eye. The presence of Said at the entrance is significant since it was his family who originally owned the Arabic bookshop.

Muna traces the connection: “The Edward Said family had bookstores in East and West Jerusalem. They ran the Palestine Educational Bookshop on Salah Eddin Street, where they sold stationery and books,” Muna told Al Jazeera.

The shop changed hands a few times. When Muna’s father, Ahmed, bought and established it in 1984, he dropped Palestine from the title, since it was illegal then to have the word ‘Palestine’ in the title of an entity or the Palestinian flag. Therefore, the name was changed to The Educational Bookshop.

The history of both bookshops is a reflection of the reading preferences of Jerusalem’s inhabitants, both locals and tourists, over the years. During the 1980s and early 1990s, the Arabic bookstore stocked mostly books in Arabic on politics, history, poetry, literature and fiction, and some English books on tourism.

A turning point came in 1994-95, when, according to Muna, many Palestinians stopped reading. “Palestinians had been reading about the supposed light at the end of the tunnel, promoted by nationalist Palestinian writers who wrote about how the peace process would bring freedom,” recalls Muna.

But after the 1993 Oslo Agreement, things changed. “It turned out to be lies, and people stopped trusting books. Consequently, the bookstore also suffered.”

Muna characterises the post-Oslo years as a time when Jerusalem received an influx of international NGO workers, diplomats and journalists. “Jerusalem’s newcomers sought to understand Palestine and the Middle East better and wanted English books. We made a conscious decision to increase our English selection.”

Therefore, Imad Muna, the eldest of the Muna brothers in charge, decided to increase the English selection of the store.

Muna still remembers the ripples created by the publication of Said’s Peace and its Discontents, published in 1996. “It was the first book to criticise the Palestinian Authority [PA], exposing the peace process and Oslo. We sold hundreds of copies in English and Arabic to Palestinians and foreigners. The PA banned it, but we could sell it since being in Jerusalem we are not under the PA.”

‘The bookshop started with one bookseller: my father. Now we are six brothers who all read, recommend and sell books,’ says Mahmoud Muna [Courtesy of the Muna Family/Al Jazeera

“We also witnessed a revival of Arabic readership during this period to which the Arabic bookstore catered.”

Muna reflected on the need to present the Palestinian story in English. “There were no proper English bookstores in Jerusalem, and the only English books were in Israeli bookshops which portrayed the Israeli viewpoint. British and American authors with orientalist perspectives were writing about Israel and there was very little on the Palestinian viewpoint. This, however, changed in the 90s.”

The English Educational Bookshop was the first of its kind in Palestine. “This was the first bookstore that sold books in English by Palestinians and about the Palestinian viewpoint,” he says.

Central to the identity of the two bookstores is their location in Jerusalem. “We want to reinforce the notion of Jerusalem as the Palestinian capital. We may expand to other areas, but our main area of functioning needs to be Jerusalem,” Muna says, acknowledging that a Jerusalem location renders it inaccessible to many Palestinians who face restrictions on entering Jerusalem.

The English bookstore also hosts cultural and literary events, such as readings, screenings, exhibitions and talks. The bookshop, according to Muna, plays a role in the larger spectrum of cultural resistance and it is being viewed as reinforcing Palestinian culture and identity.

“The Palestinians have been stripped of their rights, political representation and freedom. The last thing we have is our culture – the last wall of resistance, which Israel will find very hard to break down. The mission of the bookshop is to reinforce Palestinian culture and identity.”

The store has about 1,500 titles encompassing history, fiction, politics, poetry and even cookery. “These are serious books, not propaganda. We sell books on Palestine written in different parts of the world.”

The bookshop has titles from across the Middle East. Muna says: “This is not a Palestine-Israeli conflict; it was and is an Arab-Israeli conflict.”

The operations of the bookshop are not without hurdles, with the delivery and clearances of books often delayed. “Our books come from the US, UK, India, France, Germany, Jordan, Egypt and Spain and pass through Israeli security,” he said.

“The Israelis pick on titles. They do not like books such as the Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappe or Jeff Halper’s book on Israeli manufacture and sales of arms. They also do not like books on Hamas, or with provocative covers. The delivery of such books is delayed by two or three weeks. But since there is no censorship law over English books, no books are confiscated.”

Books from Syria, Lebanon and Iran cannot come directly. Instead, they are routed through Jordan.

They took the phones of customers and deleted pictures. “Sometimes, they spray chemical skunk gas in our neighbourhood, and the foul odours enter our store, too. We do not know if we are being targeted.”

On the positive side, Muna points out that there has been a renewal of Palestinian Arab readership. He describes the current readership as fiction preferring, predominantly female, and in the 17-22 age bracket.

“The older generation consumed mostly history and politics. The new readers like books on romance and sexuality. I want them to read more serious, classic stuff: Books on Palestinian history, Arab nationalism, Arab communism, and the great literature of the Arab world.”

“They [young readers] use social media and ask us about books we don’t know of. As a bookseller, this ought to be disconcerting, but it makes me happy.”

Source: Al Jazeera