The territory once known as Palestine was bounded on the north by Syria and Lebanon, on the west by the Mediterranean, and in the south by Egypt.

It was by geographic location a bridge – between Asia and Africa, and between the desert and the sea – and by cultural position a crossroads. The civilizations of Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, Byzantium, the Crusaders and the Arab and Ottoman empires, have all left their mark over the centuries in the mingling of empires, cultures and nationalities. Three of the world’s great religions hold this tiny territory sacred.

Arab society in Palestine prior to 1948 consisted of three main groups: the townspeople baladin, the settled farmers fellahin, and the nomadic bedouin tribes. Some 80% of the Arab population depended on agriculture, with over eight hundred villages scattered from the coastal plains to the Jordan River. Many were economically and socially independent, and difficulties in communication and environment produced strong individualistic traits within the communities: different dialects, different crops and food, different clothes.

Within the family structure roles were well defined. Women were in a subordinate position but important within the family group, being required to look after not only houses and children, but playing significant parts in agricultural activities. In some regions they were expected to work in the fields and hold responsibilities for the harvest.

In other regions there was less emphasis on agricultural participation and more time for leisure, and it was in these villages that the art of embroidery was developed.

It is difficult to discover what costumes Palestinians wore before the mid-19th century although there are some references made in the memoirs of various European travellers.

The first detailed evidence dates back to reports from missionary societies in the 1880’s whose collections of Arab costume eventually made their way to the British Museum. A study of Biblical subjects in late 19th century English painting can reveal some detailed and interesting studies of Palestinian costume. Whether these would have been worn 2000 years ago remains a moot point. The fact remains that we base our understanding of Christian traditional iconography today – Mary’s blue dress with white headscarf and Joseph’s striped coat, as typical examples – on 19th century Palestinian costume.

The majority of research done on Palestinian costume has focused on the elaborate garments made by village fellahin society for weddings and special occasions. In general, urban clothing was known to be influenced by Turkish and European fashions. During Ottoman times townsfolk wore Turkish dress, and with the rise of European influence adopted Western style outfits, modified by climate and society. By the turn of the century Beirut was functioning as the Middle East distribution point for Western clothing, from homburgs to parasols, and was distributing them in vast quantities down the coast into Palestine.

Traditional costume for men in Palestine was of very simple design and was similar in style to that worn by men throughout the Arab world. In contrast, women’s costumes, and in particular those costumes for special occasions, were regionally and stylistically diverse with great emphasis placed on ornamentation. The detailed visual elements of these costumes reflected a correspondingly detailed meaning system concerned with identity and status.

Historically both the bedouin and the fellahin women made their own costumes. While bedouin women usually bought their garment fabrics readymade, village women wove and dyed some of their fabrics. The majority were usually bought in the towns or direct from the various weaving centres in Palestine. Women would then assemble the garment and decorate it in the style of their region or village. Among both bedouin and fellahin societies, costumes would then be passed to younger members of the family. When finally outgrown or too worn to be used, a garment might be turned into household rags. Fine embroidery pieces, such as were found on the qabbeh – the embroidered chest panel of a woman’s dress – were often kept to be resewn onto new garments.

The range of textiles available for sale in Palestine was impressive: Damascus velvets, muslin from Mosul in Iraq, tabby silk from Baghdad, the finest white cotton from Baalbek in Lebanon, linen from Egypt, and silk, the Chinese secret invention that reached the Middle East on it’s way to Europe. Local fabrics favoured for Palestinian costumes were handwoven silks, cottons and linens. Cotton was historically cultivated in Palestine but from the mid-19th century onwards locally produced fabrics tended to be woven from yarns imported from Egypt, Syria and England. Garments were also made from wool bought from the bedouin tribes, although the bedouin themselves did not weave clothing.

The weaving centres of Palestine were at Majdel and Gaza in the south, and Safad in northern Palestine with the towns of Nablus, Ramallah and Bethlehem also producing some fabrics. Palestinian weaving never developed to the artistic or technical level of neighbouring Syria and the industry declined noticeably after the introduction of machine-made mass produced textiles from Europe. It did, however, produce a range of garment fabrics specifically for village fashions.

Dyeing was a profession carried on by only a few families who kept formulas secret. Indigo was the most important dye for Palestinian costumes. Most women wore an everyday dress of indigo blue, but the dye was also used for men’s clothing and women’s headveils. The plant was grown in the Ghor area of the Jordan Valley, but stocks were later supplemented with imports from India. Saffron, for yellow, was grown in the villages. Sumac was used for a yellow-green colour. Red colour was obtained either from madder, or from cochineal or chermes insects mixed with pomegranate. Synthetic dyes reached the Palestinian market from Germany early in the 20th century, appearing in local markets around 1912. Many people still continued with their natural dyes but by the 1920’s the industry was in a sharp decline.

The metallic threads used in couching work from the Bethlehem and Jerusalem areas were made in Aleppo from cords of silver or gilt silver. Originally, couching cords were of spun silk, but after the First World War most were imported and were factory made of artificial silk. The thinness of the older type was still preferred for precision work.

The style of clothing worn by fellahin women was established by regional preferences and local social factors. Many of the basic garments maintained an over all similarity in design, if not in decoration. Fellahin costume consisted of the basic dress thob, pants libas, jacket jubbeh, and coat jillayeh. The thob, as with male costume, was generally a loose fitting robe with sleeves with the actual cut of the garment varying by region. Decoration on the thob was concentrated mainly on the square chest panel qabbeh, the cuffs and top of the sleeves, and vertical panels running down the dress from waist level. Some regions decorated a lower back panel of the dress known as the shinyar. Jackets and coats were usually kept for special occasions and were richly decorated according to local customs. Similar garments were sometimes worn by town women, although usually of better fabric and hybrid decoration styles. Unlike bedouin women, the fellahin did not veil their face except on their wedding day. Various styles of veils were developed to cover the hair, as were intricate headdresses heavily ornamented with coins.

Girls were taught dressmaking skills usually from about the age of eight. Much importance was placed on embroidery, as it was thought that a prospective bride’s character and personality were revealed through her work. By the time of one’s wedding it was expected that a bridal outfit be completed, as well as items embroidered for the home. The wedding costumes of Palestine were ornate and symbolic and consisted of the heavily decorated wedding dress and accessories together with valuable coin which covered headdresses and many pieces of silver jewellery. The style of the bridal dress, as well as garments for everyday wear, was determined by the regional style.

To understand the distribution of embroidery styles in Palestine, Shelagh Weir, author of the publications Palestinian costume (1989) and Palestinian embroidery (1970 and 1988), requests one to imagine the country divided by two horizontal lines: the first placed south of Mount Carmel and the Sea of Galilee at the level of ‘Afula, and the second running from the coast to the Jordan River north of Jaffa and south of Nablus. Her research has shown that in the area between these two lines there is very little history of embroidery (although still showing traditions of fine decoration, including braidwork and appliqué, in women’s costume) and an Arab proverb found in this region, originally recording by Gustav Dalman in 1937, that “embroidery signifies a lack of work” certainly backs Weir’s findings. The areas where Weir found a long standing tradition of embroidery were in the area north of her top line, in Upper and Lower Galilee, and in the area south of the bottom line, in the Judean Hills and on the coastal plain.

A myriad of embroidery stitches were popular in Palestine. While cross stitch has come to be thought of as the most commonly used stitch throughout the country – with the couching stitch favoured in the Bethlehem region following in popularity – some areas, such as the Galilee, favoured a mixture of cross stitch, satin stitch, stem stitch and hem stitching. The gold and silver cord and fine silk thread couching produced in Bethlehem and neighbouring villages was so popular that wedding costumes featuring this type of embroidery were produced commercially by the women of Bethlehem for weddings throughout the country. Both Gustav Dalman in 1937 and Hilma Granqvist in 1931 record wedding songs in which Bethlehem wedding dresses are mentioned:

“God knows that our outfit today

A hundred ‘royal’ robes which we have cut

For the bride to whom we are betrothed.

God knows – today is our outfit

A green and a ‘royal’ [malak] dress we have bought

For the bride to whom we are betrothed!

Ten jackets [taqsireh] have we bought

For the beloved ones in order to appease her”

(Hilda Granqvist Marriage conditions in a Palestinian village vol.2 1931: p.42)

In southern Palestine and the Sinai Desert, cross stitch was certainly the preferred decorative technique, with either silk or cotton thread.

Motifs favoured in Palestinian embroidery and costume were also diverse. Palestine’s position on the international trade routes certainly exposed it to influences from diverse fields. Weir argues that cross stitch motifs may have been derived from oriental carpets, while couching motifs may have it’s origin in the vestments of Christian priests or the gold thread work of Byzantium (1970: pp.13-14). Research by Hanan Munayyer of the Palestinian Heritage Foundation reveals that some popular Palestinian motifs may have been in use in the region and in neighbouring Egypt since the fourth century AD. Munayyer also notes that the importance of Syrian textiles on Palestinian styles should not be overlooked (“New Images, Old Patterns: a historical glimpse” ARAMCO news Mar/Apr 1977: pp.5,7,9). Leila el Khalidi, in The Art of Palestinian Embroidery (2000), proposes a more global assimilation and selection of motifs.

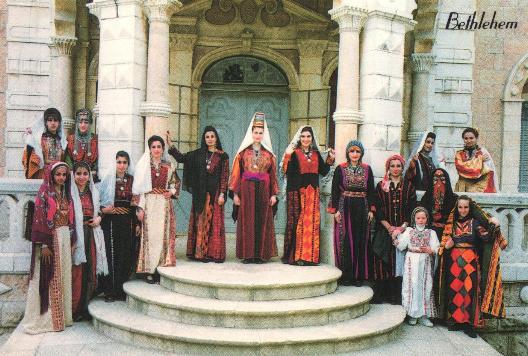

Postcard of a variety of Palestinian regional costume (pre 1948) from the collection of Maha Saca, Director, Palestinian Heritage Centre, Bethlehem

Whatever their source, Palestinian embroidery motifs and patterns are of great intricacy and diversity. Again, their popularity was defined regionally, with certain designs being indicative of certain villages. Other motifs, such as the cypress tree saru, are found throughout Palestine in many different forms, some complex, some simple. In fact, many Palestinian motifs can be seen on analysis to be derived from quite basic geometric forms such as triangles, squares and rosettes. New patterns introduced into Palestine in the late 1930s, via European pattern books or magazines, promoted the appeal of curvilinear motifs such as flower and vine or leaf arrangements, and introduced motifs such as the paired birds which became very popular in central Palestinian regions. Geometric motifs maintained their popularity in the Galilee and southern regions, including the Sinai Desert.

For detailed study and illustration of Palestinian motifs we recommend Leila el Khalidi’s The Art of Palestinian Embroidery (Saqi Books, London 2000), Shelagh Weir and Serene Shahid’s Palestinian embroidery (British Museum, London, 1988) and Jehan Rajab’s Palestinian costume (Keegan Paul, London 1989). The Palestine Costume Archive will be adding a file to this website illustrating motifs at a later date.

Source:

istic of all modern colonial-settler states, but usually accomplished once the indigenous people in question has been eliminated, dispossessed, or otherwise seemingly defeated therefore making it safe to do so. The colonial-settler state of “Israel,” established on the ruins of Palestine and through the expulsion of the majority of its indigenous population in 1948 and after, is no different.

istic of all modern colonial-settler states, but usually accomplished once the indigenous people in question has been eliminated, dispossessed, or otherwise seemingly defeated therefore making it safe to do so. The colonial-settler state of “Israel,” established on the ruins of Palestine and through the expulsion of the majority of its indigenous population in 1948 and after, is no different.